I’m not sure if it was thinking about being in the back seat of a car driven by my high school track coach smiling devilishly as he swerved and circled through the near empty snow covered Northeastern University parking lot; or it was running into my senior English teacher while on my Cape Cod honeymoon with my young bride almost a year to the day following my high school graduation. But those human intersections popped up as I pondered the question , “ How did I get here?” ‘Here’ was a summer professional development day for our staff. The keynote session was led by Julia Freeland Fisher, researcher and author of Who You Know, Unlocking Innovations That Expand Students’ Networks. ‘Here’ was me, a 30+ year educator now in a leadership role at a cutting edge virtual school.

Thinking about the question, I began to recall the many social network intersections of my youth and formative professional years that led to opportunity. As compelling as Freeland Fisher’s message was about expanding student networks and mentoring connected to student interests, I felt it was only part of an equation for getting to a point in one’s life translating to satisfaction and happiness. Another part? Good adult modeling. The type of modeling Ted and Nancy Sizer alluded to in his book, The Students Are Watching: Schools and the Moral Contract. I had a wealth of both and would argue that all students need mentoring, modeling, and networking opportunities. It’s a key to unlocking a student’s passion and joy for learning and understanding what motivates him or her to take advantage of possibilities as they are presented.

As I thought about ‘how did I get here?’ a bit more, the picture began to sharpen. My happiest years professionally were teaching English and coaching. In high school nothing about my average grades shouted college material for anyone viewing my report cards. In fact, my high school guidance counselor went as far as telling me she didn’t think I had demonstrated a readiness for college. It would have been easy to have been lost in the sea of 1,372 graduates of my school, but I had lifelines thrown to me along the way.

My parents had expectations that I would go to college, but their full time supermarket jobs provided little time to connect to my academic or adolescent worlds. Their own school experience, which included one high school diploma earned in 1941 by my mother, offered no road map for navigating through high school successfully. However, I had a bounty of adults who showed me the way; who opened doors of possibility all throughout my school experience and early professional career. But as I dug deeper into the questions, ‘How did I get here? How did I travel the path of an educational career that included teaching, coaching and administration?’, my mind drifted to my high school track coach and 12th grade English teacher.

I didn’t really have favorite subjects in high school, but did favor teachers who made subjects interesting. In some cases teachers who made subjects attention-grabbing didn’t necessarily teach the material well. For example, my parents thought I was a math savant because of my ‘A’ grades in Algebra II. But the teacher, who was fired for going rouge on a Boston field trip, made the subject too fun. To this day I find that Algebra confounds me; and it didn’t help me as a near failing first year accounting major at Northeastern University. If it wasn’t for my freshman writing course, I may have flunked my way out of college. At the time, it seemed an unlikely lifeline, but it was a result of those intersections with Miss Andem a year earlier.

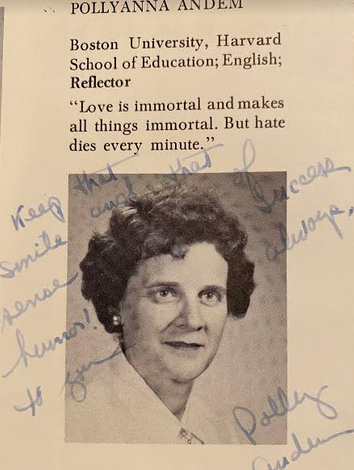

Pollyanna Andem was a petite woman with a soft demeanor and calming voice. A combination that didn’t typically command a classroom never mind the lecture hall I sat in with over 100 high school students. Standing behind a podium, one could only see her from the shoulders up. She had a spinster look; closely cropped curly hair; thin wire rimmed glasses; and was always impeccably dressed. But her relaxed energy and assuring tones helped draw me in. Miss Andem was anything but a spinster; she was effortlessly hip and conveyed joy. She was even able to make vocabulary and grammar interesting by somehow bringing “story” into a dry lesson. Her happiness to be sharing 5th period English with us was evident each day. As I found out decades later while reading her obituary, teaching was her life. She was never married and had a very small family that included one predeceased sister and a niece. She taught well over 4,000 students though out her 40+ year career and I imagine, as she did for me, opened up unlimited pathways of possibilities over a lifetime.

There were three interactions however that kept Miss Andem at the forefront of my memory for teachers who made an impact. The first was that she knew me, which was no small feat. Alphabetically, I sat in the back of the large lecture hall, one of the several classes she taught each day. I needed to ask her a question after class one day and as I approached her somewhat nervously at her podium on the way out of class, I was startled that she knew my name. It made an impact. I wasn’t any more than an average student grade-wise, which meant that she must be observing something beyond the grades and lecture hall mundaneness to know her students. Later that year, she was one of the few teachers I asked to sign my yearbook. In it she wrote, “Keep that smile and sense of humor. Success to you always.” Miss Andem saw me, one of her many students, as pleasant, likable. She opened a door to see a side of myself that I hadn’t previously thought about. In reflection, this is the true, subtle power of a teacher. It’s likely no coincidence too that the highest grades earned my senior year were in English.

During the second semester of my senior year, I had a study hall from which I was consistently getting a pass out of to go to the gym, where my teacher/track coach, Mr. O’leary would let me hang out. Early in the semester on my way to the gym, I passed one of Miss Andem’s smaller classes. It was a Shakespeare elective as it turned out and one day I decided to step in the room and take a seat in the rear of the room, perhaps initially to impress other students with my boldness. My immaturity was on display, but she went on uninterrupted, continuing a discussion with students on the Merchant of Venice. I was drawn in and returned the next day…and the next. Miss Andem eventually wrote me a permanent pass to her class which I unofficially audited. Not having to worry about a test or a grade, it was the first Shakespeare learning experience I enjoyed. It ultimately better prepared me for the rigors of two semesters of Shakespeare that I needed to take as an English major at Northeastern University a few years later.

As pleasant as my interactions were with Miss Andem in high school, my final intersection with her proved to be the most awkward. I ran into her along a touristy shopping area in Hyannis almost a year from the day of my high school graduation. I was on my honeymoon, a topic for another memoir. She was on her summer break. My first thought was seeing a former teacher in a relaxed state out of school wearing shorts and a floral blouse seemed like an absolute contradiction. My second thought was her totally pale complexion also seemed out of place for a summer day on Cape Cod. She stuck out in the tanned crowd on the sidewalk, and to my surprise she recognized me saying hello using my name. That relaxed me a bit and I introduced my young wife, who was pregnant, but not showing at that point. My relaxation turned to nervousness as I saw the worrying concern in her eyes as she sized up the situation. Like most adults at the time, the thought of being married at 19 usually didn’t end well. I let her know though that I had switched majors to English education and hoped to be a teacher. The calming or perhaps a nervous smile that I recognized appeared and she wished me well, but I’m not sure she held out much hope. In retrospect, while I’m not one for regrets, I wish that I had reconnected professionally with Miss Andem during my teaching journey.

Everything about my high school track coach and physical education teacher, Mr. O’leary, seemed to come naturally except for his thinning slicked back hair style. His smile and movement were seemingly constant which could lead to a student being relaxed and out of breath at the same time as evidenced by a typical PE class. We would immediately start jogging to warm up while he took attendance and then move directly to the daily activity. Never stopping, except for brief teaching moments to explain a movement, a rule or an expectation. And in those brief moments, his soft spokenness conveyed confidence. His voice assured a level of success even though there were various levels of results. His constant smile often turned into a quirky grin indicating we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously.

That ability to convey confidence carried over as a track coach interacting with athletes. His mantra of “Practice like a champion and you may become one,” was not a pronouncement often expressed, but each day at practice it was understood. To use a cliché, our actions spoke louder than our words and that translated to team state championships for my three years in high school. But his impact went well beyond his superior coaching abilities. Track teams were generally large rosters filled with students of all abilities. Generally, there were no cuts…no one was eliminated who wanted to be there. No matter one’s talent, Mr. O’leary found a way to individually connect with students for them to positively contribute to the team in what was largely an individual sport. If someone was elite, he positioned them to reach or sometimes exceed their potential. If someone struggled, he put them in a position to contribute to a team win. It seemed everyone felt good about themselves on the bus ride home from a meet.

My first one to one conversation with Mr.O’leary occurred in 10th grade following the last round of basketball tryouts. Basketball was my love and vying for one of 12 or 15 roster spots on the team was part political and part ability. I knew I was on the margins and perhaps Mr. O’leary did too. His office was just off the locker room and he called me in following tryouts. I didn’t know what to expect, but he leveled with me. He said I had the potential to compete as a track and field athlete beyond high school if I committed to it more and ran during both the winter and spring seasons. It meant eliminating basketball. I’m still not sure of the psychology that was at play, but he offered to let the basketball coach know if I preferred to take the track route. I had been running track successfully since junior high school and enjoyed it; enjoyed the coaches too. I hedged my bets a bit, thinking track was a better pathway to college. As it turned out, it was.

It also turned out that spending three years with Coach O’leary paid dividends well beyond college scholarship opportunities. It exposed me to coaching as an art form; to the notion that coaching was teaching; and perhaps most critical that teaching itself was knowing your students and their challenges both inside and outside the classroom. I ultimately taught English and coached basketball for a majority of my professional career before turning to administration as a school principal and assistant superintendent. No matter what role, teacher or administrator, I still saw coaching principles as a leadership advantage as I attempted to build community and collaboration. Needing to spend nights, weekends and summers to take teams of players to activities like camps on college campuses; or teams of teachers to a conference was no different from Coach O’leary taking our relay team to a meet in New York City or him driving us through that snow covered parking lot to prepare for that meet. He showed us how growth and improvement was a process; and that process had to include an element of joy. Those lessons played a critical role in many of the life choices I made.

Everyone needs someone who knows them beyond a name and a seat assignment in school. I was fortunate to often have teachers of that ilk. But as I’m closer to retirement than my mandatory school years, two teachers entered the equation of my life and professional success when pondering the question, “How did I get here?” Had it been another teacher rather than Miss Andem as I randomly dropped int her class, I may have been sent to the office for discipline; but in her own way, she nurtured an undiscovered interest for me. Mr. O’leary, with his honest conversation regarding basketball and track, helped me see a side of teaching and coaching that opened a door for me to choose a path to travel; to think about and explore a career as a teacher and coach. I appreciated each more for the human side of what they shared with me more than what they were able to teach me. I saw a perspective of a teacher that I liked, one to which I wanted to aspire. Knowing them and having them know me was a key piece of the puzzle that helped me make decisions about my future…switching majors from business to English education following my freshman year of college despite family whispers of concern that it was a mistake; connecting to a network of people through my college coop experience whom I crossed paths with over a 30 year career; and remodeling the behaviors they practiced in my own professional experience because it made me happy and fulfilled with my work.

I too have crossed paths with thousands of students throughout my career in education. Reflecting on my own journey, I wonder about the scope of my impact with students and colleagues over the years. Miss Andem and Mr. O’leary never explicitly knew the impact their connection had on me. Hopefully I was able to pay it forward with both the students and colleagues that shared my teaching and learning space. Perhaps Miss Andem and Mr. O’leary are still providing a sense of understanding for me that teachers who authentically connect with their students do make a difference…explicitly and implicitly.